By Sue Palmer, The Horse Physio

Prefer to listen? Click on the video above. If you enjoy reading, keep scrolling. You can support my work by buying me a coffee, joining the Healthy Humans, Happy Horses online learning hub, or signing up to my newsletter. Remember to follow, like, and share on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. Please note that this may contain affiliate links. Thank you – your support means so much!

A new study in the Equine Veterinary Journal has highlighted something many of us who work hands-on with horses recognise daily: spinal dysfunction is extremely common in ridden horses, even those who aren’t showing overt signs of pain. The research team examined 492 showjumping horses and found that not one was free from spinal articular dysfunction .

For horse owners, this is important—not because it is something to fear, but because it helps us understand how much work our horses’ bodies do and how sensitive and adaptive the spine is. When we appreciate that, we can make wiser, kinder choices about training, management, and when to seek help.

As an ACPAT and RAMP Registered Chartered Physiotherapist, much of my day-to-day work is about supporting horses exactly in these areas: restoring ease of movement, reducing barriers to performance, and helping horses feel comfortable in their bodies.

What the Study Looked At

Over three years, chiropractic records were analysed from routine and performance-related examinations. Each horse had 30 spinal motion units assessed, from the poll (C1) to the lumbosacral junction. The aim was to map where dysfunctions were most common and whether age or other factors influenced their prevalence.

The horses weren’t selected because they had severe problems. Many were simply being checked for stiffness, reduced suppleness, occasional unevenness, or performance plateaus—the kinds of subtle issues owners often notice without being able to put a finger on the cause.

Every Horse Had Some Degree of Spinal Dysfunction

One of the clearest findings was that:

This doesn’t mean every horse was in pain. Instead, it reflects the natural strain placed on the body of an equine athlete. Just as no ballet dancer has a “perfectly free” spine every day, neither does a horse who jumps, schools, hacks, or carries a rider.

Where Were the Main Problem Areas?

The most commonly affected vertebrae were:

These areas make perfect biomechanical sense:

The study reinforces what we see clinically: discomfort or restriction in one part of the spine often shows up as tension or unevenness somewhere else.

Younger vs. Older Horses

Younger horses (under six) had significantly fewer dysfunctional segments in the cervical spine than older horses (15+)—consistent with what we know about degenerative changes and the increased loading of the neck over time.

Warmbloods, who formed the majority of the study group, are already somewhat predisposed to cervical osteoarthritis due to their conformation, so this finding is especially relevant for many sport horses.

Pain Isn’t Always Obvious

Perhaps one of the most helpful points for owners is this:

The horses who did show pain presented with:

This mirrors what I wrote in Brain, Pain or Training?: many horses with discomfort don’t “look lame” or “look in pain”—their behaviour tells the story first.

Why This Matters in My Work as a Physiotherapist

Reading this study felt like scientific validation of something I have felt in my hands for decades.

Much of my treatment time is spent improving the flow of movement through the spine, from poll to tail. That fluidity is essential for the limbs to move freely, the muscles to work without resistance, and the whole body to function with ease.

To an untrained eye, it may sometimes look as though I am focusing on “the neck” or “one spot”. But in truth, my hands are always listening to the entire spine. The spine is never just one segment—it’s a long, flowing, continuous chain. Freeing movement in one area almost always brings release somewhere else.

I’m deeply involved in the feel beneath my hands:

the quality of the tissue, the ease of motion, the absence of resistance, the softening that comes when a “stuck” area finally lets go.

And when it does?

There’s simply no feeling like it.

I know instantly that the horse is going to feel the difference.

So often, that’s followed by:

These moments are one of the many reasons I love this work so much. They’re the horse’s way of saying, “Yes. That helped. Thank you.”

What This Means for You and Your Horse

This study helps us appreciate how normal spinal dysfunction is, even in horses performing well. It isn’t a sign of “something wrong”—it’s a sign that your horse is living, moving, working, and adapting.

What matters most is:

If you enjoy supporting your horse’s comfort at home, my book Horse Massage for Horse Owners and the accompanying online course offer practical techniques to help improve flexibility and softness through the body—skills any horse owner can learn.

Reference: Patricio CR et al. (2025). Spinal articular dysfunction is common in athletic horses. Equine Vet J. 57(5):1357–1362.

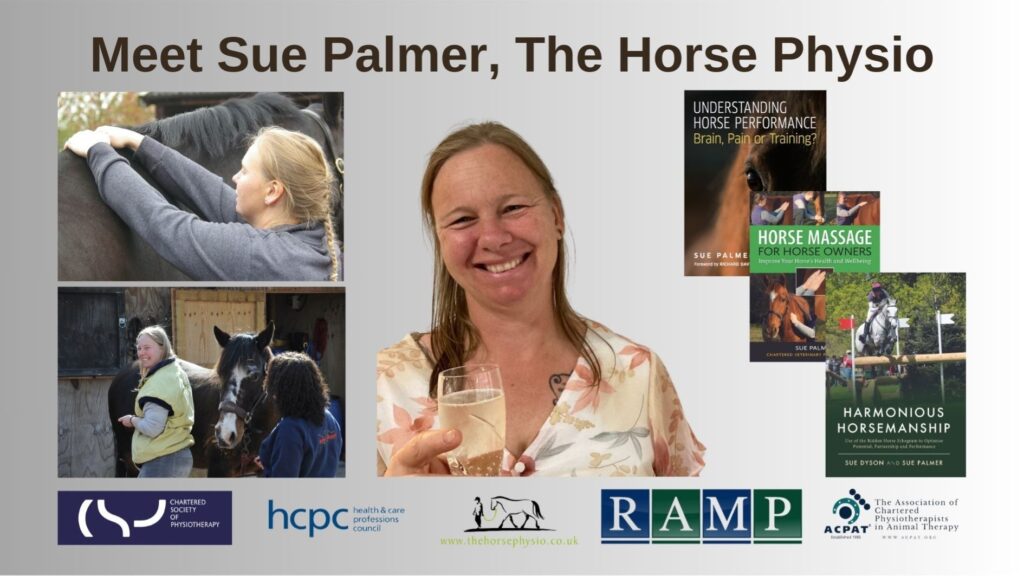

🌟 About Sue Palmer, The Horse Physio

Sue Palmer MCSP is an award-winning Chartered Physiotherapist, educator, and author. Known for her compassionate, evidence-informed approach, Sue specialises in human health and equine well-being, with a focus on the links between pain and behaviour in horses. She is registered with the RAMP, ACPAT, IHA, CSP, and the HCPC.

📚 Books include:

Harmonious Horsemanship (with Dr Sue Dyson)

Understanding Horse Performance: Brain, Pain or Training?

Horse Massage for Horse Owners

Drawn to Horses (with illustrations by Sarah Brown)

🌐 Learn more at www.thehorsephysio.co.uk